This is an overview of how handwriting can be developed quickly within a school that I wrote to support the Specialist Leaders in English team in the Wirral a couple of years ago.

Handwriting development is about being IPC – insistent, persistent and consistent.

Subject leadership in literacy often needs the same approach!

Handwriting Handbook- Wirral 2024/25

Contents

Why does handwriting matter?. 2

Handwriting Teaching in a Nutshell 2

A process for exploring handwriting in school 4

Introduction

Handwriting is consistently a challenge in schools. However, it is a crucial skill, that children need to acquire. Handwriting matters!

The Presentation Effect was verified by a meta-analysis of studies that have tested this theory. They found that a less legible version of a paper will be scored much more harshly than a more legible one (Graham, Harris & Hebert 2011).

Neat handwriting makes a reader more likely to award a higher mark. Poor handwriting has the reverse effect. With either scenario, the mark assigned may not accurately reflect the quality of information and ideas it contains (Santangelo and Graham 2016).

Handwriting consumes an inordinate amount of cognitive effort – at least until it becomes automatic and fluent (Graham, Harris & Hebert 2011). It is suggested that when we automatise handwriting, we can focus on other aspects of writing, like planning and composition. And we are less likely to forget what we were going to say next.

The National Curriculum (2014) states that writing using a joined script should be the norm by Years 3 and 4. Pupils should be able to write with pace, so they can record their thoughts (DfE, 2014, p.34). Handwriting should continue to be taught, with the aim of increasing the fluency with which pupils are able to write down what they want to say. This, in turn, will support their composition and spelling (DfE, 2014, p.39).

It is suggested that soon as children are able to join letters, they should use this for all of their written work so that it gradually becomes automatic (Education Endowment Foundation 2020, p.38).

Why does handwriting matter?

A meta-analysis by Santangelo and Graham (2016) considered whether teaching handwriting enhances writing performance. They examined the results of 80 experiments.

Two questions they asked were:

• Does handwriting instruction improve handwriting legibility and fluency?

• Does handwriting instruction improve writing performance?

The answer to both questions was yes.

They found that teaching handwriting results in statistically greater legibility and fluency. It produced statistically significant gains in the quality and length of pupils’ writing too (Santangelo & Graham, 2016) .

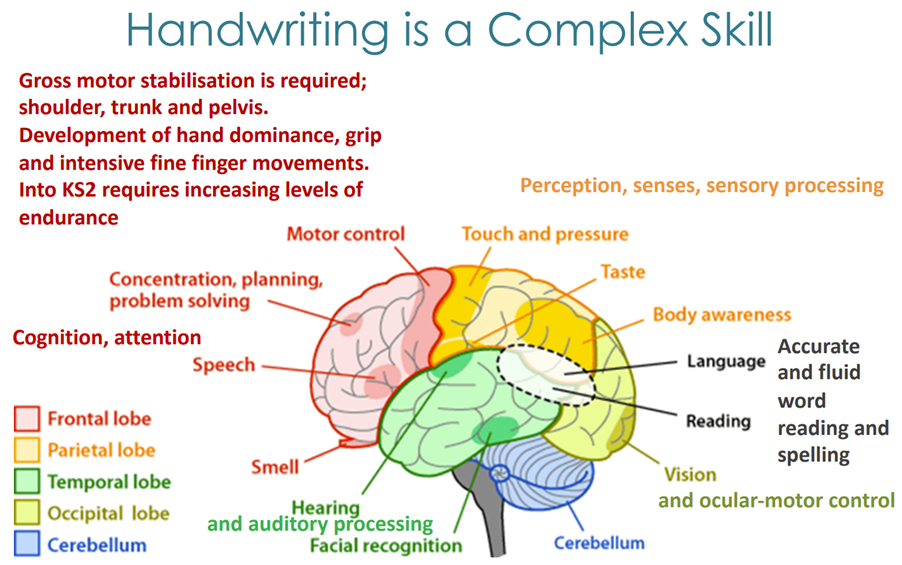

Joined handwriting has been shown to help train the brain to be able to integrate visual and tactile information with fine motor skills (James & Atwood, 2009). It has been shown to activate the motor, visual and linguistic areas of the brain and has a direct relationship with improving maths, spelling and science outcomes in older students.

When studying older students, Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014) showed that taking notes longhand, through writing, improved reading comprehension.

Developing Fine Motor Skills

Fine motor movements are small muscle movements requiring a close eye-hand coordination.

Handwriting Teaching in a Nutshell

- Stick to un-joined letters initially. These are easier to learn as they require fewer strokes and changes in direction.

- Introduce learning to join in Year 2 – once the previous outcomes of correct shape, size, and spacing are well established.

- Avoid giving joined-up handwriting elevated status in the classroom. Or else some children may feel pressured to try joining before they are ready.

- Encourage children who are struggling with the coordination required for joining to focus on improving the legibility and fluency of a basic un-joined style first.

They’re also keen to highlight that writing in a fully joined style can inhibit handwriting fluency. A mixed style has, in fact, been shown to be quicker.

The national curriculum says that joined up handwriting should be the norm by Years 3 and 4. Pupils should be able to use it fast enough to keep pace with what they want to say (Department for Education 2014, p.34). Handwriting should continue to be taught, with the aim of increasing the fluency with which pupils are able to write down what they want to say. This, in turn, will support their composition and spelling (Department for Education 2014, p.39).

As soon as children are able to join letters, they should use this for all of their written work so that it gradually becomes automatic (Education Endowment Foundation 2020, p.38).

Handwriting practice should be extensive, supported by effective feedback and motivational and engaging. A large amount of regular practice is required for pupils to achieve fluency and this can be supported with teachers providing feedback to help pupils focus their effort appropriately.

- Ensure the child is ready to write (can they draw kisses correctly?)

Encourage lots of large motor and fine motor movements such as climbing and cutting with scissors.* - Teach how to make the letter shapes

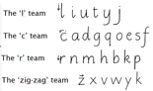

Use single letters with exit strokes and ensure the child knows which movement group each letter belongs to. Teach by demonstration and observing the children’s practice. Young children can make their letters in sand, paste etc before using pens or pencils. - Teach capital letters and use for names, e.g. Oliver

Capitals are as tall as h, l, b etc and do not join to the other letters in a word.* - Write letters on a single line

The tails of g, p, etc should hang below the line. - Teach the relative size of letters

Give the three sizes names: attic (h, b, etc), room (a, e, etc), cellar (g, y, etc) or sky, grass, underground. - Show how words need a small space between them

Please do not use a finger as a spacer – a lolly stick or piece of card is better. * - Teach how to join the letters

At this stage omit joining after g, y, j, x, z.* - Encourage writing at increasing speed

Introduce loops to y, g, j to increase fluency, and make other individual modifications. - Encourage self evaluation of handwriting using the ‘S’ Factors

These are sitting, size, shape, spacing, slant, stringing (i.e. joining) and speed.

* Only proceed beyond the star if the earlier stages have been understood and are used in practice. Stage 6 is probably better addressed in Year 5 or above (age 9/10).

Alongside the above

Encourage good habits of posture and pen hold (‘P’ checks). The dynamic tripod is a very efficient way of holding a pen/pencil (pen held between forefinger and thumb with the third finger behind) but it does not suit all children. Comfort and ease of movement are more important.

Assessing handwriting

Formative assessment

Summative assessment

A process for exploring handwriting in school

The way handwriting is taught in school is important. Ensuring there is progression, consistency and persistence in the teaching of handwriting is often a valuable quick win in developing the reading and writing skills of children. The development of pre-handwriting skills in Early Years and Reception is essential. The gross and fine motor skills of children should be developed in a systematic way across the year. Teachers should be aware of how children’s strengths and skills are developing and respond accordingly, but adjusting their provision and planning.

There are many programmes and resources that can be drawn upon to support gross and fine motor control in the early years.

This four- step process for exploring the teaching and learning of spelling in a school can be completed in a couple of hours. It starts with a meeting with subject leaders, finding out about their aims and current concerns, before looking at the school environment and analysing independent writing. Finally, the findings are drawn together and an action plan co-constructed with the school team to develop practice.

Step 1. Meeting with Literacy/Writing Leaders

At the start, it is important to meet with the subject leaders and explore how the handwriting curriculum is organised and their views on how effective it is. The Subject Leader Review document can be used to structure the conversation.

The Subject Leader Review.

Q1. How is handwriting taught?

What age/phase does explicit handwriting teaching start? What pre-handwriting programmes are in place? How does PE and Art feed into the development of children’s gross and fine motor skills?

What schemes/curriculum materials are used?

How often/for how long?

Q2. How is handwriting assessed?

How reliable and valid are the assessments used (if there are any assessments used at all?

How are they used to support children’s learning?

Q3. How do they know? (monitoring)

How frequently is handwriting taught?

Are the children on track with their handwriting skills? Are there explicit expectations of what the children are able to do at the end of each year?

Q4. How does the handwriting curriculum progress in terms of learning from EYs to Yr 6?

Is it sequenced?

Does it follow the NC2014 expectations?

Q5. How do the children’s handwriting skills progress from EYs to Yr 6? Cohorts that are strong? Areas of weak progress/attainment?

What interventions are in place to support children who make slower progress?

Q7. When did staff engage in any professional learning about handwriting?

What did they cover?

What are leaders’ evaluations of the subject/pedagogical content knowledge of teachers regarding handwriting? How do they know?

Q8. Where are the most pressing challenges or areas of concern?

What would leaders find helpful?

Step 2. Learning/Environment walk.

With the Subject Leader, walk around the school and notice the environment. Things to notice include:

- What does the classroom environment look like? Are there presentation prompts and resources to support handwriting? Are they visible and accessible?

- What do displays of the children’s writing show?

- How is English discussed and displayed around school? Is it clearly a reading/writing school?

Step 3 – diagnostic analysis of handwriting

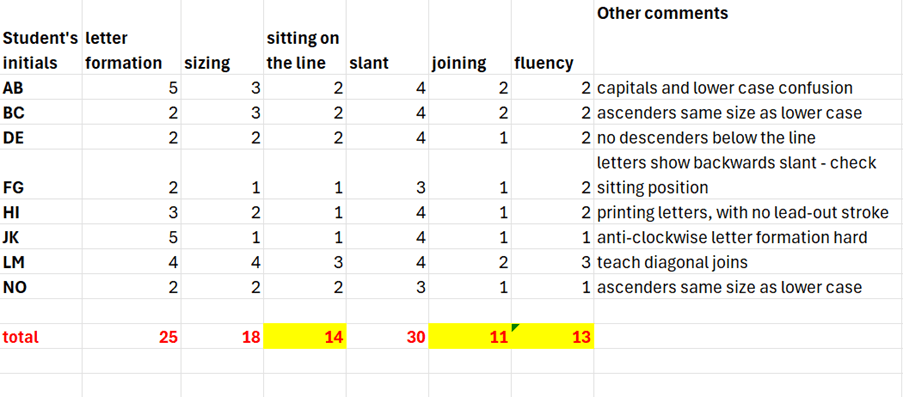

A diagnostic analysis of student handwriting provides both a clear picture of students’ strengths and weaknesses in Handwriting and a clear direction for instruction. The assessment should be an opportunity to evaluate students’ control of letter formation (upper- and lower-case letters), sizing, positioning on the line, joining, spacing and fluency.

Handwriting can be analysed from independent writing the children have produced, or from dictated sentences and short passages that have been designed to include a all letters of the alphabet (.

To get a picture of what children know and have learnt, analysing an independent piece of writing is powerful.

How to analyse the handwriting in an independent writing sample.

- Identify a piece of independent writing the children have all written. Ensure there was as little support as possible. If this is not possible, conduct a timed test, where the children are asked to write a sentence as many times as they can in 3 minutes.

- Analyse the letter formation and fluency using a scale of 1-5 (1= very poor, 5= excellent). Decide on a score for letter formation, sizing, sitting on the line, slant, joining and fluency.

- The analysis of handwriting patterns can lead to a bespoke handwriting catch-up curriculum and help with reviewing the effectiveness and progression of teaching and learning in the curriculum.

Step 4 – Collating a picture of spelling in the school

Drawing on all the evidence collected, consider the strengths and weaknesses of the teaching and learning in school. The 3 main questions to answer are:

- How effective is the curriculum?

- How effective is the teaching? How successful are the children at handwriting? Do the majority of the children develop their skills as expected?

- How knowledgeable are the staff? Both in the strategies they use to teach and the way they support children to develop their skills.

The answers to these questions will enable an action plan for development to be constructed. There are a range of different approaches and strategies that can be used.

| Developing the Curriculum | Considering the progression within the curriculum – is it consistent and develops? Are end of year expectations understood? Refreshing the handwriting policy and planning (ensuring coverage is understood by all) Ensuring appropriate resources are easily available Ensuring pathways for intervention are in place. Cross curricular approaches for developing gross and fine motor skills (PE, playground games and resources, Art and D/T curriculum, and focus on physical development in Eys and KS1) |

| Developing teaching and learning | Monitoring of teaching Team planning and teaching Handwriting analysis of children’s independent work to inform intervention and catch up teaching at the point of need Regular meetings to share pedagogies and intervention approaches. |

| Developing subject and pedagogical content knowledge | CPD to develop an understanding of the complexities of handwriting and its development Introduction of different pedagogies Cross-year group observations Team teaching Co – planning following assessment of children Implementing spelling interventions such as Cued-spelling |

References

James, K. H., & Atwood, T. P. (2009). The role of sensorimotor learning in the perception of letter-like forms: Tracking the causes of neural specialization for letters. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 26(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643290802425914

Santangelo, T., & Graham, S. (2016). A Comprehensive Meta-analysis of Handwriting Instruction. In Educational Psychology Review (Vol. 28, Issue 2). Educational Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9335-1